Written by John Madara & Dave White Tricker; produced by Quincy Jones

Mercury 72206 1963 Billboard: # 2

207. IRENE CARA, "Out Here On My Own"

Written by Michael Gore & Lesley Gore; produced by Michael Gore & Gil Askey

RSO 1048 1980 Billboard: # 19

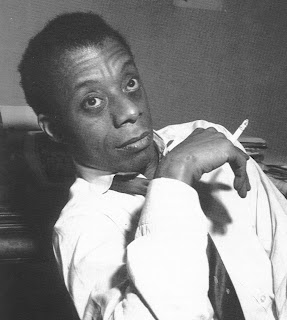

In my last post, I referred to Sheila Weller's wonderful book Girls like Us, which uses the parallel lives of Carole King, Joni Mitchell, and Carly Simon (not to mention many of their friends) to tell the story of feminism's adoption and transformation by a whole generation of American women during the last four decades of the twentieth century. It's an absorbing book and one that I have few quarrels with. On reflection, though, I wonder what Weller might have made of Lesley Gore. Catch me in the right moment and I might be tempted to call Gore the James Baldwin of Feminist Pop.

Let me explain. For many, Lesley Gore is a punchline, of course, merely typical of the manufactured teen sweethearts of the supposedly dead years in [white] American pop, the years between Elvis' induction into the United States Army and the Beatles' first appearance on the Ed Sullivan show. (You will note, of course, that those two presumed benchmarks stress the departure and arrival of male performers.) Gore's songs, we are told, are treacle, crying about parties and singing about lollipops and such.

But at least on the strength of its subject matter, I would defend "You Don't Own Me" as an important song for its historical moment. If we measure it against two other prominent 1963 releases featuring female vocals, well then, yes, "You Don't Own Me" may not be as bold a song as "Don't Make Me Over," Bacharach & David's valentine to Dionne Warwick's refusal to be remade for pop success, but it's no the Angels' "My Boyfriend's Back" either. How many other songs that year granted such a challenging and empowering voice to a seventeen year old girl? In this case, the song is more radical because the singer is a girl and not a woman: she's asserting her independence from boys even before she understands the importance of securing independence from men. And I would point out that she is doing so in the same year that Betty Friedan's The Feminist Mystique is first published.

Like most of Gore's best work, this track is produced by Quincy Jones. While it's not necessarily one of his most complex productions, the eerie tone he lends the verses grants a little more depth through shadow to the triumphant singalongs on the choruses. When Joan Jett covered the song almost twenty years later on her first album with the Blackhearts, she essentially duplicated this arrangement, transposing it from a pre-British Invasion pop orchestra to a post-garage band rock and roll outfit.

Why the analogy to James Baldwin, though? Well, the 1960s as they unfolded were not necessarily kind to James Baldwin, much in the way that they were not necessarily that kind to Lesley Gore. Baldwin's first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, was a critical and popular success in 1953, but his second novel, the exquisite Giovanni's Room, met with bewilderment in most quarters when it appeared in 1956. Why? Because Go Tell It on the Mountain was an autobiographical novel about the role of religion in African American life, while Giovanni's Room was about a doomed love affair in Paris--between two white men. From his first published story, Baldwin was classified as a "black" writer, and "black" writers are supposed to write about "black" subjects. As the 1950s gave way to the 1960s, as the Civil Rights era gave way to the moment of Black Power's ascendance, Baldwin also started to be rejected by a number of prominent African Americans. Some movement leaders questioned whether Baldwin was too "accomodationist," "white," or "effeminate" to represent black manhood to white America. To most such challenges, Baldwin's response had been that, like most of the novelists he respected and emulated, the only thing that he was trying to represent in his fiction was humanity.

Well, the 1960s as they unfolded were not necessarily kind to James Baldwin, much in the way that they were not necessarily that kind to Lesley Gore. Baldwin's first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, was a critical and popular success in 1953, but his second novel, the exquisite Giovanni's Room, met with bewilderment in most quarters when it appeared in 1956. Why? Because Go Tell It on the Mountain was an autobiographical novel about the role of religion in African American life, while Giovanni's Room was about a doomed love affair in Paris--between two white men. From his first published story, Baldwin was classified as a "black" writer, and "black" writers are supposed to write about "black" subjects. As the 1950s gave way to the 1960s, as the Civil Rights era gave way to the moment of Black Power's ascendance, Baldwin also started to be rejected by a number of prominent African Americans. Some movement leaders questioned whether Baldwin was too "accomodationist," "white," or "effeminate" to represent black manhood to white America. To most such challenges, Baldwin's response had been that, like most of the novelists he respected and emulated, the only thing that he was trying to represent in his fiction was humanity.

Still don't see the connection to Lesley Gore? Just wait a decade or two. During the 1980s, both Baldwin and Gore went through something of a renaissance, and it's not too much of a stretch to say that the sudden interest in both artists had to do with a much freer discussion within popular culture of same-sex relationships. For Lesley Gore was lesbian, as James Baldwin was gay, but a pop music star's sexual preferences had been even more closely guarded during the early 1960s than an esteemed novelist's would have been. But suddenly in the 1980s, when Gore's sexual preference was now more widely known, her songs were being covered on record by Joan Jett and she was being interviewed for Ms. by k d lang. No longer solely viewed as an embarrassing stereotypical throwback, she came to be seen by many as a trailblazing pioneer in female pop.

This reappreciation of Gore surely reached its apotheosis in Grace of My Heart, Alison Anders' wonderful 1996 fictional film about a woman songwriter in the 1960s and 1970s whose narrative journey through those years very closely follows the life story of Carole King. At one point, the film's protagonist (Ileana Douglas) and another songwriter of whom she may be jealous (Patsy Kensit) are forced to collaborate on a song for a squeaky clean early 60s teen pop star named Kelly Porter (Bridget Fonda). They're stuck for a subject, until they overhear the popstar having an argument with her girlfriend. They end up writing a song for Porter called "My Secret Love," which allows her to proudly but covertly pay tribute to the same lover that industry publicity demands she must hide from her adoring public.

At one point, the film's protagonist (Ileana Douglas) and another songwriter of whom she may be jealous (Patsy Kensit) are forced to collaborate on a song for a squeaky clean early 60s teen pop star named Kelly Porter (Bridget Fonda). They're stuck for a subject, until they overhear the popstar having an argument with her girlfriend. They end up writing a song for Porter called "My Secret Love," which allows her to proudly but covertly pay tribute to the same lover that industry publicity demands she must hide from her adoring public.

Of course, Douglas and Kensit didn't really write "My Secret Love," but do you want to guess who did? That's right: Lesley Gore, in collaboration with, among others, David Baerwald of David + David. At the age of forty-five, she helped write the song that everyone now wished she had sung at seventeen, with a chorus that is an almost direct steal from "You Don't Own Me."

You may notice, though, that that's not the second song I've listed here. Instead, I've paired Gore's greatest single with a song she didn't sing on record, a single from Fame that most viewers of the film probably didn't connect with the pretty blonde from almost two decades before who sang "It's My Party" and did a guest shot on Batman. But Gore, who actually cowrote the lyrics for the song to her brother Michael's music, saw "Out Here on My Own" as a sequel to "You Don't Own Me" (which she didn't write) and frequently performed the two songs together as a medley during her comeback concerts of the 1980s.

It's easy to see why. If "You Don't Own Me" is a girl's wouldbe grownup declaration of independence, "Out Here on My Own" is a young woman's more knowing acknowledgement that, even if freedom is both real and vital, independence in its literal sense is pretty much impossible. Gore's lyrics may at first glance seem generic, but in a way that's part of their beauty. Within the movie, they comment on a romantic relationship, but they could just as well be part of a conversation between friends. This song isn't about sex, gay or straight. It's about the fact that, once you've worked hard to win the freedom of full adulthood, it's even harder to give up part of it to someone else. When you're raised to feel incomplete in and of yourself, to feel like an accessory, mature love and trust often feel like backsliding.

A bold cry for freedom, and the confusion of realizing that you can't do everything alone--with two songs, Lesley Gore bookends the initial triumph and continuing challenges posed by modern American feminism. But I'm not sure she'd ever get credit for it.

-Frontal.jpg)

_04.jpg)